My Year of Reading 'War & Peace'

All that Tolstoy's novel led me to, the two most memorable (and chilling) scenes from the novel, and how I am beginning to sight 'War and Peace' in other novels

Towards the end of 2023, I realised I wanted to shake up my reading life by introducing to it something that would be far from the effect that my writing personas have had on it1.

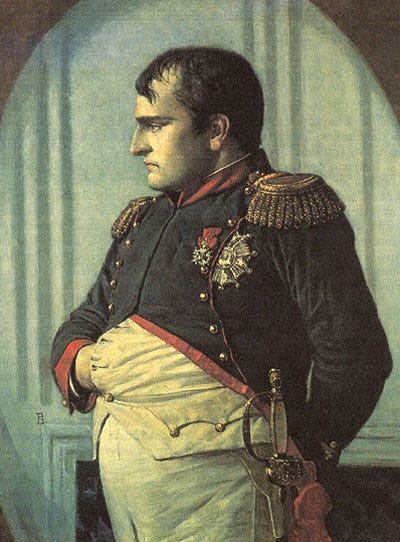

’s War & Peace readalong popped up at the right time. I joined it, and, over twelve months, just as I had expected and desired, Tolstoy’s fat novel sent me on new mental pathways, some exploratory, some critical, and all of them leaving a creative remainder—which is another way of saying that it changed my life.My initial plan was to write a recap post every month, a plan that I adhered to till the end of April. May onwards, my writing about my reading of War & Peace nearly stopped. Part of it was due to a phenomenon I am not alien to: life stepping in in project-smashing ways, as it is wont to. But part of it was also because the explorations I was on by then were so informed by the novel’s plots (the plural here is deliberate) and its historical context that the writing demanded an insider-reader, one who had already read or was reading the novel, or one who was at least interested in the era of Napoleonic wars. I had grown obsessed, I must also confess, about the glaring contradictions in post-revolution France’s imperial expansionism, its attack on the minds and militaries of other European empires used to fattening themselves through one or another form of slavery (Russia was an ur-empire in that sense). I came close, not kidding, to commencing on Walter Scott’s nine-volume biography of Napoleon, and I even looked for an English translation of Thiers history of Napoleon’s invasion of Russia (a source for Tolstoy, though much derided by the Russian for its Bonapartist slant). Not writing monthly Substack posts helped me avoid the cultivation of outright obsessions, my curiosities thus fed at levels not too far beyond healthy.

But it’s not possible to read War and Peace and not have your reading list and your viewing list altered. Desirous of knowing the French Revolution better, I watched Andrzej Wajda’s Danton and Robert Enrico’s two-part La Révolution Française (both excellent, both on Youtube), and then, to know Napoleon better, I watched Ridley Scott’s film (deplorable)2. For 2025, I have resolved to be part of Simon Haisell’s readalong for Hilary Mantel’s A Place of Greater Safety, a novel about the three key figures of the French Revolution: Camille Desmoulins, George-Jacques Danton, and Maximilien Robespierre. On the Russian side of things, I watched Sergei Bondarchuk’s seven-hour adaptation of Tolstoy’s novel, and allowed myself not a small amount of amazement at the scale of the film and its very existence, given that War and Peace is a novel that arguably humanises Russian aristocracy, a slant that doesn’t exactly align with what we think of the Russian Revolution and the USSR3. For 2025, I have resolved to read Isaac Babel’s Red Cavalry, Boris Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago, and Vasily Grossman’s Life and Fate. I am most excited by the prospect of reading the last one, which also means, to my mind, a movement towards the 21st century.

There are numerous unforgettable passages and sequences in War and Peace. There are soirees and balls in Petersburg, a wolf-hunting episode in rural Russia, an expedition for purchasing horses, a botched elopement, a cross-dressing Christmas celebration, proposals for marriage, marital spats, a duel in a field of snow, afternoons of gentrified boredom, philosophical conversations, an initiation to a sect, and, of course, dozens and dozens of episodes from the various battles that the novel is interested in, right from the Battle of Austerlitz in 1805 to the Battle of Borodino in 1812. In scenes of a certain scale, and by scale I mean both a multitude of characters and a multitude of spaces and sub-spaces, Tolstoy initially affords us an omniscient narrator, who details soiree set-ups in a ballroom or military formations across miles of landscape to light up our visual imagination, and even goes into commentary and judgment. After the scene is set, Tolstoy zooms in on a particular character, an operation in which he reveals himself as fond of catching a character either in anticipation at the cusp of an action or in bewildered self-enquiry at its conclusion4. In all of this, Tolstoy’s selection of what to describe and pinch and dilate is always impeccable. In my reading life, no other author has come close to this simultaneity of comfort with both the general-panoramic and the specific-private.

Although Tolstoy’s treatment of the Battle of Borodino, where for a length of time he even views things from Napoleon’s perspective, is often cited as extraordinary, the parts of the novel where Tolstoy delivers two of his best scenes, according to me, come after the battle. This is when the Russian army under Field Marshal Kutuzov decides not to continue warring after the gruesome day at Borodino (68,000 dead or wounded on both sides in a single day5), effectively leaving Moscow, the Russian empire’s ancient capital, to its fate. The Grande Armée marches in to Moscow, where Napoleon waits for Tsar Alexander’s note of surrender. The note never arrives, and after five weeks, the French decide to retreat, the Russian autumn already turning to hoary winter.

The first scene is of a lynching. Holding mayoral duties in Moscow during war-time, a certain Count Rastopchin has been keeping public morale high through a pamphlet of sorts. Sentiments like fighting till the bitter end and not giving up Moscow at any cost and citizens must prepare to fight are what the pamphlet is made of. So when Rastopchin comprehends Kutuzov’s decision and its implications, foremost among them being the hard fact that Moscow will have to be abandoned, his situation with the city’s populace becomes tender. An angry mob turns up at Rastopchin’s door as he himself prepares to leave Moscow. To this mob, Rastopchin offers a prey named Vereshchagin, a political prisoner.

“Lads!’ said he [Rastopchin], with a metallic ring in his voice. ‘This man, Vereshchagin, is the scoundrel by whose doing Moscow is perishing.”

[...]

“He has betrayed his Tsar and his country, he has gone over to Bonaparte. He alone of all the Russians has disgraced the Russian name, he has caused Moscow to perish,’ said Rastopchin in a sharp, even voice, but suddenly he glanced down at Vereshchagin who continued to stand in the same submissive attitude. As if inflamed by the sight, he raised his arm and addressed the people, almost shouting:

‘Deal with him as you think fit! I hand him over to you.”

The mob beats Vereshchagin to death. Immediately after that, Tolstoy gives us voices from the mob, some of which are—astonishingly—critical of the crime just committed. Later, even Rastopchin repents the matter briefly, a feeling that he suppresses with threads of reason, articulated in his interiority in French, including the line “Il fallait apaiser le peuple. Bien d’autres victimes ont péri et périssent pour le bien publique” (“The people had to be appeased. Many other victims have perished and are perishing for the public good”).

The scene of Vereshchagin’s violent death, and Rastopchin’s linking of it with appeasement and public good, shook me, mostly because I could relate it to instances of lynching in India today. In Moscow in 1812, there was at least a clear perceptible threat (Napoleon); in north India, an imaginary threat is enough to lead to such action. Misinformation and moral weakness are, however, the common elements.

Tolstoy is particularly conscious, in fact, of the power of rumour, misinformation, and gossip all through the novel. That he begins the novel in a high-society salon in Petersburg, grounded in the link between polite chatter and social capital, is early proof. In the aristocracy Tolstoy enlivens, news of misbehaviour by young women travels fast enough, and with no need for investigation into the reasons or methods of transmission. Everyone knows when a teenaged girl’s engagement breaks; everyone knows when a woman cheats on her husband. Tolstoy understands how such narratives are formed and propagated in closed societies. His genius, though, is to extend the schema to the armed forces as well. In the appendix in my edition, he articulates a point he illustrates (and labours on) all through the novel: how battles and wars are complex and infinitely varied events, lending themselves to no easy narrative, and how narrative-formation essentially happens after an unsaid all-party settlement regarding the objectives of such a narrative (and after the initial aid of hyperbole and gossip).

Two or three days later the reports begin to be handed in. Gossips begin to narrate how things happened which they did not see; finally a general report is drawn up, and on this report the general opinion of the army is formed. Everyone is glad to exchange his own doubts and questionings for this deceptive, but clear and always flattering, presentation. Question a month or two later a man who was in the battle, and you will no longer feel in this account the raw, vital material that was there before, but he will answer according to the report.

The second scene that captivated me, and is likely never to be erased from my memory, is that of an execution. This happens during Napoleon’s five-week stay in Moscow, when fires start to come up all over the city. The French, troubled by the developing inferno, start to make prisoners of any Russians they can still find in the city, and those suspected of arson are to be executed.

Tolstoy's description of the execution—rows of condemned men, pits dug for corpses, burial without caring whether the shot person was dead or alive—seem to anticipate the horrors of the century next, and ours as well.

Pierre Bezukhov, a rich young aristocrat and the most important character in the novel, is among those caught and lined up for execution. He finds himself sixth in the row of the condemned. When the man in front of Pierre is taken to be tied up to a pole and shot, we see things from Pierre’s perspective:

When they began to blindfold him he himself adjusted the knot which hurt the back of his head; then when they propped him against the bloodstained post, he leaned back and, not being comfortable in that position, straightened himself, adjusted his feet, and leaned back again more comfortably. Pierre did not take his eyes from him and did not miss his slightest movement.

That the man adjusted his knot himself, and then, a moment later, tried to find a comfortable position for his neck—he is to be shot the next moment!—is Tolstoy giving us a streak of the outré element from that repertoire called Human Nature. The reader’s attention coagulates at this moment, and one silently commends Tolstoy for being alert to that possibility.

Later, I discovered that James Wood, in his criticism, has returned to this precise moment at least a couple of times. In one essay, he calls the man’s behaviour ‘life-surplus, pushing itself beyond death.’ In another essay, he sees this man as a literary ancestor to George Orwell’s condemned man in ‘A Hanging’, one who steps aside to avoid stepping into a puddle even as he is being taken to be hung.

I understand that from now on my reading life will include sightings of War and Peace in other novels.

In Vasily Grossman’s Life and Fate (tr. Robert Chandler), which I have already started reading, such a sighting is to be expected, given the novel’s reputation as the War and Peace of the 20th century. I made the sighting early enough—in the first few chapters, in fact. Just like Tolstoy did with War and Peace, Grossman begins his novel in a multi-character, multi-lingual set up. There is a smattering of French, for example, in the early pages of Grossman’s novel, just as there was in Tolstoy’s novel. In both beginnings, judgements are passed and suggestions floated up, the latter in the hope of them becoming rumours and acquiring a certain power, even if that power led only to self-gratification. But there is one key difference, and it is a big one: instead of a high-society soiree, Grossman’s opening milieu is a German concentration camp.

Tolstoy didn’t have the word for it, but all that he said in War and Peace about Napoleon—including the vehement essayistic rejection of the man’s military genius and the many novelistic illustrations of his pettiness and self-importance—amount to stating one thing clearly: Napoleon was a proto-fascist. And so, without the word for it, Tolstoy sets up the novel of grand historical events and personages as a counter-narrative against simplistic History and the common recurring delusion of the superman. If you share the view, you might want to give yourself your own year of War and Peace.

I wrote about how I came to War and Peace at length, in my first post about the novel.

I realise that my opinion was more balanced right after watching the film

Ridley Scott's Napoleon, and Tolstoy's

Earlier this month I was in Bali, Indonesia for a short holiday. On the return flight to Delhi, I picked Ridley Scott's Napoleon from the in-flight entertainment assortment. Why? Because of my running status of being a serious War & Peace reader. The bulk of Tolstoy’s bulky novel is set between Napoleon's war with Russia and Austria in 1805 (culminating…

That Lenin approved of the novel and found it amenable to the notion of revolution (I read the essay in which he described why), must have helped matters there.

I wrote at length about how the Tolstoyan character is transitory, ever-curious about the mechanics of change, and the magic of the state-shift between I-as-I-am-now and I-as-I-was-earlier

Month #3 of 'War and Peace'

Simon Haisell at Footnotes and Tangents is hosting two readalongs for 2024: one for Leo Tolstoy’s War & Peace and the other for Hilary Mantel’s Cromwell trilogy. I’m participating in both. This post is a stringing together of my notes, observations, and fancies as I read Tolstoy’s bulky novel. It is the third of twelve such planned monthly instalments. Reading these posts do…

A historian compared it to a "a fully-loaded 747 crashing, with no survivors, every 5 minutes for eight hours".

Nice! Yes I also gave up on trying to describe what exactly was happening in the Mahabharata, because it involved giving so much context that I felt it wouldn't be that fun for the reader. Excited to hear how Life and Fate goes--has been on my list for ages, but haven't attempted it yet because of the length