How specific are the places to which writers belong?

Reflections after an interview with 'Cities in Fiction'

A month or so back, I was interviewed over email by Apoorva Saini, co-founder of the archival project called Cities in Fiction. A brief description of the project’s aims and its call for participation, in its own words:

Through this project, we want to encourage learners and educators to experiment and see ‘fiction as a method’. Add all kinds of places you encounter in fiction to our archive. Villages, towns, small, big, mega cities, cosmopolitans, and the in between, whatever be their nature: forgotten; existing; or proposed. As the project develops with your help, we hope to provide ready resources that anyone could use, especially those building curriculums and pedagogies around cities.

Apoorva’s questions were the best set I have been asked in an interview. They seemed to me to form a kind of enquiry that is less a task for the interviewer and more a culmination of the (natural, and rare) processes of paying attention. I felt wholly invited to talk about the various facets of my creative practice (including as Founder Editor of The Bombay Literary Magazine). You can read the whole interview here.

In one of her questions, Apoorva invited me to fill a blank in the [Tanuj Solanki * _________] formulation—with the name of a city. It was a simple ask: where was Tanuj Solanki the writer from? where did his fiction come from? There are many pragmatic reasons to avoid answering that question: I’ve lived in five cities for significant periods; all have felt like home. I didn’t fill in the blank. I answered the question in the following, non-committal way:

I think the idea is somewhat limiting. I’ve written more about Mumbai than about Muzaffarnagar. I now live in Gurugram, so at some point, it may enter my fiction too. But I guess if one has had the kind of childhood where a lot of growing up happened in one place, then one is tied to that place. In my case, it would be Muzaffarnagar, with the caveat that I may have other places appear more frequently in my fiction, and with the acknowledgement that I’m always writing from Muzaffarnagar. I think it’s a question that can be answered in various ways—which place has formed your sensibility the most, which place do you feel most like saving from oblivion, or which place do you know the best? This can change over time.

But a segment of my own response (emphasised above) has kept coming back to me.

So then, which place do I feel like saving most from oblivion?

This one:

This is a view of… well… the bricklaid driveway (can this be called driveway?) and the front kitchen garden from the porch/portico of the last bungalow in Muzaffarnagar that my father was given by his employer, the sugarcane research department of the Uttar Pradesh government. Last, because my father died in it on January 1, 2015 and my mother had to move out of it within six months of his death. A government house isn’t permanent, of course.

This house and its parts have appeared many times in my fiction. My last short story on this substack, Odd Time, was set here. Half of that story was written in this house in 2014. The concluding half was written after my interview with Apoorva in December 2023. I think the interview was the reason why I went back it.

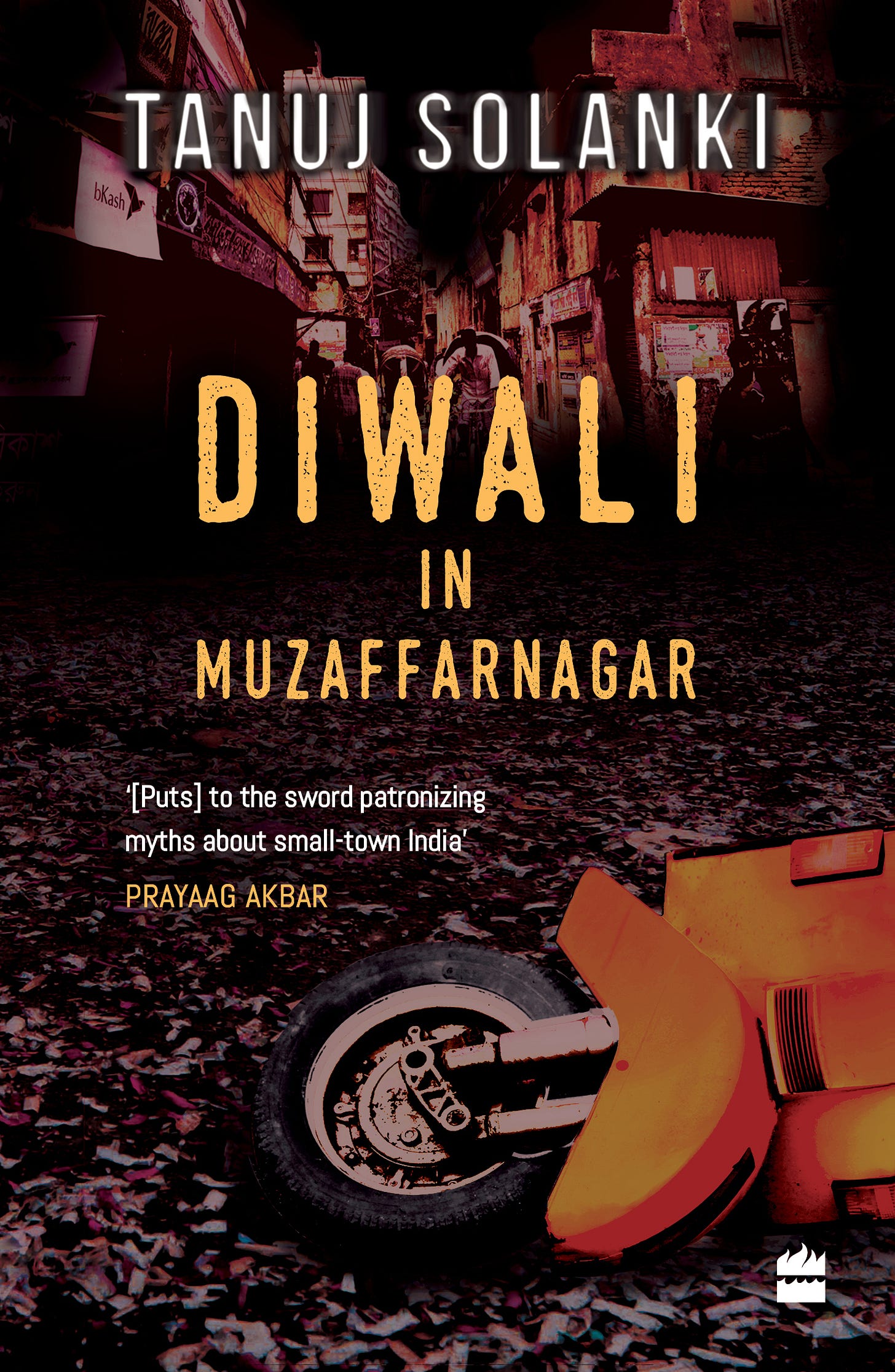

In my short-story collection, Diwali in Muzaffarnagar, a ceiling fan from this house, ‘from an era when a lot of iron went into those things’1, is transported to a flat in Mumbai and becomes the fan from which the young poet Dilip Singh—from the story The Sad Unknowability of Dilip Singh—hangs himself to death.

In another story titled Compassionate Grounds, the protagonist Gunjan arrives at the same driveway after her father’s death and finds it packed with relatives and mourners:

Outside the bungalow now were a dozen or more cars parked on either side of the road. A driveway descended from the road and ran for fifteen or so metres before being halted by a small portico-like space. Next to the driveway, running along the length of the house, was a kitchen garden. There were groups of men standing all along the driveway […] Most people trampled the radish in the garden. Gunjan knew it had been planted by her father.

The verandah in the title story is also from this house; it’s where the Diwali puja happens:

All of us then got out of the room and walked to the little temple that Mother had assembled just outside the kitchen. Father had to help Grandfather get there. Many twinkling diyas adorned the temple – all Mother’s labour. The idols sparkled in the diyas’ quivering light. Mother placed marigold petals and some rice in our hands. These pooja rituals were among my earliest memories of my family. But now the gods had little to give, and I wondered if any of us really believed that a prayer could answer anything. We anyway sang the hymns that every Hindu household knows how to.

The house doesn’t satisfy one part of my response to Apoorva: it is not that my childhood memories are tied to it. I was 24 when my parents moved here from another government-given residence (which was, incidentally, not even a hundred meters away), and 28 when my mother had to vacate it. In the intervening years I visited the house only on holidays—Holi and Diwali. But given how frequently I try to memorialise this house through my fiction, it definitely appears to be the place that I feel most like saving from oblivion. Is it so because this house is the place that helped form my sensibility the most? But my sensibility of what? Of being a writer? I became one—to the extent one ever becomes a fiction writer—between the ages of 24 and 28, in the years when my parents were living in this house. It was in those years that I wrote the bulk of the stories that became the published collection in 2018 (I was 32 when that happened). But most of this writing happened in Mumbai, where I lived happily without any particular pangs of homesickness. In Odd Time, I created a character who’s homesick for this house while being inside this house. That is one reason I call it fiction. Because that’s not me, that was never me.

But do I remember things as clearly as I think I do? What if I don’t? What if the house was home in all meanings and manners of the word during significant years, when on weekdays I grappled with the big city and the job and on evenings and weekends did the writing that actually made me a writer?

The truth is that I miss this house today. I don’t have enough photos of it. There is no chance I’ll ever step inside it again. Some other family lives in it now. One day they will have to vacate it for yet another family. And so on and so on. A government house isn’t permanent, of course.

My sincerest response to Apoorva, I realize, might be to fill the blank in the following way: [Tanuj Solanki * the flat-roofed bungalow at the last corner in the government-run sugarcane research centre in Muzaffarnagar]. But then, her project is Cities in Fiction, not Houses in Fiction, not ‘Houses in which one’s parents have lived and in which one of them has died’ in Fiction.

I repeated, I think exactly, this description for the ceiling fan in Odd Time.