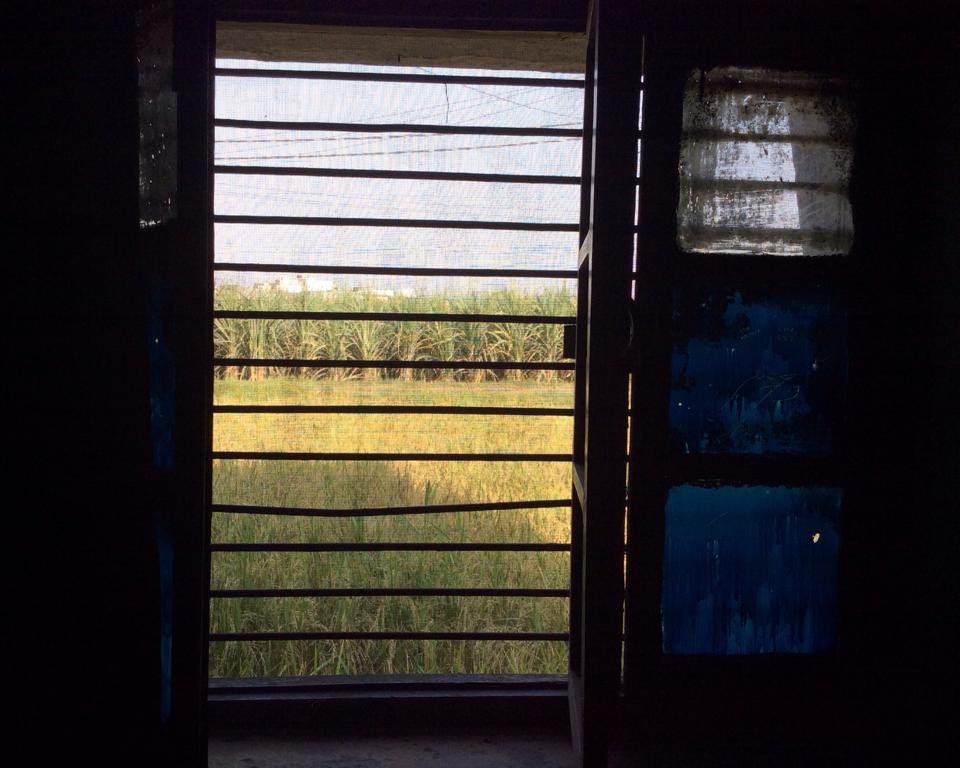

The last day of September 2014. I am sitting in a plastic chair in a room inside my father’s government-given bungalow. This room becomes my room whenever I am here in Muzaffarnagar, Uttar Pradesh, my hometown, which I left eleven years ago when I was seventeen. It is close to eleven am. I’m content after eating mother-made aloo paranthas in what may be termed brunch and I’m thus thereafter sitting on the chair just about flatulently, leafing through my copy of Joyce’s Ulysses, which I picked up ten or so minutes back from a carton full of books. The carton lies semi-open to my right on the floor, its top two flaps at angles of thirty degrees and sixty degrees roughly respectively. As of now I am tilting my chair backwards. The carton and the books inside it belong to me. It is one of two literature-filled cartons I had to send to Muzaffarnagar from Mumbai after the break-up with Annabelle forced me to move to a smaller place and manage my belongings, et cetera. I note that it is not exactly very clear whether the first word in Ulysses—‘Stately’—is used as an adjective or an adverb. My legs are on the edge of the single bed opposite the chair; pushing. As always in Muzaffarnagar, I feel relaxed yet prone to melancholy, suffering from homesickness that registers as sad simply because it is complexly manifesting here, here in the epicentre of what is home for me for all emotional purposes. I’ve read this copy of Ulysses till page 139, which is a number I’m surprised I can recall, for my last rendezvous with the book was close to twelve months back and happened during a shoddy time for me, to put it softly. I’ve also read Molly Bloom’s punctuation-less buzz at the end, which is about sixty crazy pages if I remember correctly. I don’t think I can say I understood the point of it. I register that minor spasm of guilt for never pushing hard enough to finish this book, which is effectively the first acknowledgement I’ve made to myself in this stint of reading that I’m about to give up again. But the ineluctable modality of guilt is that of diffusion, in a way that the specific source is lost and one is left with low-intensity greyness about everything under the sun: losing Annabelle, losing a job, regaining a job, losing Muzaffarnagar yet again, coming back only for vacations, and so now here again feeling homesick but so while at home. I stop tilting the chair and pull my legs back from the bed. I place them on the cool floor and look to the window to my right. For no reason except perhaps a desire to move away from feelings through the effort of observation, I inspect the elements of my view minutely. I see. There is a single mullion that asymmetrically divides the window in a two-third one-third ratio. There is a gauze/netting that bars mosquitoes and other insects from entering the house while also providing excellent silhouette opportunities for geckos who seem to love that sort of thing. There are second-class-railway-compartment-window-like horizontal iron bars that have no real purpose except probably that of preventing direct human dermal contact with the gauze/netting. It occurs to me that using the word mullion to describe the vertical partitioning of space in this window is to seriously offend the word mullion, actually. The three panels in the window each have three square-shaped glass panes. I notice, for the first time, that the square window panes are painted. This discovery is a tad thrilling because it makes some neurons in my brain go like: ‘How come we didn’t notice this ever?’ I repeat: the window panes are not coloured glass but painted glass. I can see many large brushstrokes of blue. The thus shaded panes perform the task of blocking the sun’s superfluous rays, which must be great, I imagine, although I cannot remember ever noting the amount of sun that usually enters the room from that direction. There is no doubt it was my father who painted these panes. The greenery outside the window has two sections: (1) the upper halves of paddy stalks closer to the window and (2) the sugarcane plants in the distance. The contrast between the greenery outside and the blue panes is striking and near-beautiful and makes the same neurons dismayed again. But the window panels’ wood is splintered here and there and has certainly had some history with termites, all of which lends a sort of decrepitude to the almost-beauty before my eyes. It feels as if the green and healthy place outside is being peeked at from a tired, old, about-to-come-to-ruin frame. Kind of like Christina’s World but in the reverse. I once asked my father which year this house was made in, a question to which he responded with a vague and not-really-helpful ‘Much before the nineties, for sure.’ Actually, to place its construction even before the eighties is not too difficult. The house embodies something about Socialism, I feel. It has a solid and functional look but is not exactly solidly built. The elements in the house betray the state’s heavy hand just as an Ambassador chugging on the road does. In the bathrooms, conspicuous pipes feed heavy brass taps of a kind impossible to find today in Mumbai or even in Muzaffarnagar. Some of these taps have to be tied with twine to prevent leakage. There are fluted cuboidal conduits on the walls carrying electricity wires inside them; the space between each flute is full of ages-old spider web components and other general dirt and gecko poo and soot etc. The kitchen and bathroom drains run through the backyard and are open by design. The backyard has standing-brick paving that my parents call khadanja, as opposed to flat-brick paving that they call padanja. Two heavy ceiling fans from a time when a lot of metal went into those things hang in two rooms; they are too cumbersome to be handled by one person alone, and so I suspect that nobody has ever touched those fans since the day they were installed. There are recessed shelves in the concrete walls in all the rooms. I remember the shelves in the drawing room used as display cabinets, but with time the purpose they’ve come to serve is to hold keys and letters and a bottle of massage oil or an inhaler or other things. In the verandah, the shelves next to the washbasin house shaving tools in one mug and toothpaste and toothbrushes in another mug. In the room I’m sitting in, the shelves are wider and stacked with my younger brother’s twelfth-standard PCM books. The fattest among these books are Physics by Resnick & Halliday and Organic Chemistry by Morrison & Boyd. Both these books are classics, in the true sense of the word; I used both when I was in +2 twelve years back. I wonder which is the bigger classic: Joyce’s Ulysses or Morrison & Boyd’s Organic Chemistry? I’m somewhat amused by the question. I use the amusement to drop Ulysses on the bed and walk up to the shelf to pick up Organic Chemistry. I open the tome at random, and the page splashes me with diagrams about Benzene’s unique structure. Seeing a particular diagram, I follow through a line of reasoning with delectable recognition—I am, once again, aware of how the molecular hexagon of Benzene has a particular solidity because of the orbitals coming together to form a sort of superorbital both above and below the hexagon. ‘I knew so much,’ I whisper to myself. Then I step out of the room and ask my mother if she’d like a cup of tea.

*

On the morning of January 1, 2015, three months after the day I dumped Ulysses yet another time and re-learned that thing about the Benzene molecule, my father died of a heart attack, his first and last one.

I was at my apartment in Mumbai. It was a Thursday. I received a call at six in the morning from my father’s sister, who was in the house in Muzaffarnagar at the time. She said my father was sick. She said I needed to come home immediately. When I asked to speak with my mother, she made an excuse. I knew what had happened, though I abstained from saying it, both to myself and to my aunt.

The earliest BOM-DEL flight I could catch was at 10 in the morning. But it got delayed. Fog in Delhi. The flight took off at 1 p.m. I got several calls from my aunt while I waited for the flight. In one of them, she cryingly said, ‘Please come quickly.’ She didn’t once tell me that Papa had died. I called my boss and told him I had to go home because my father had died. He told me that I should take as much time as I needed to. As I cut that call, I felt stupid. What if Papa hadn’t died? Was I assuming things?

A car was waiting for me at Delhi airport. My mother’s sister, her husband, and their two children. We started towards Muzaffarnagar. I remember the ride as a silent one. About two hours into it—we must have crossed Meerut—my eight-year-old cousin tugged at my shoulder and said: ‘You know your father has died?’ His mother shushed him. I smiled at him and turned to look ahead at the road flying by. It really was flying by, as were the roadside eucalyptus trees and the sugar cane fields behind. The sun hung low like an orange lozenge. The sky was dim as my sentiment.

We reached too late. My father had already been cremated. The pyre was lit by my brother. Till today, whenever I have to win an argument against my mother, I use the fact that she did not ask the posse of relatives and well-wishers and self-appointed experts in rituals to wait one day for the elder son to come and do the final rites for his father. She regrets nothing in her life more than she regrets this. If I take this route, I always get my way.

*

It so happened that the place where I shed my first and only tears for my father was the same room where, just three months ago, I had abandoned Ulysses in favour of Organic Chemistry. In the days after my father’s death, as I stayed on in Muzaffarnagar, the room became mine again. I picked up Organic Chemistry on the day the wake ended, learned a thing or two about ethanol, and vowed to get myself drunk at the first opportunity. It was told to us that the house would need to be vacated within six months. When I left for Mumbai a few days later, leaving my ill-prepared mother with the task of finding her next abode, it was with the awareness that I’d never see this house—and this room—again. Till today, whenever she has to win an argument against me, she cites how I practically abandoned her after my father’s death, how she had to find a place in Muzaffarnagar all by herself, how she had to shift between houses all by herself, how she had to deal with the emotional churn all by herself. If she takes this route, she always gets her way.

I have never seen that copy of Organic Chemistry by Morrison & Boyd again. The Ulysses has somehow found its way to me. I still haven’t moved past page 139.

*

The first day of 2024. It’s exactly nine years since my father died. I am sitting in an ergonomic chair in a room inside my three-room apartment in Gurugram. This is the room I write in. This is one of several rooms I have written in over the years. There was that single room in Mumbai where, next to the small desk abutting the queen-sized bed, I wrote several of my first stories and my first novel. Then I got married, a year and fifteen days after my father’s death, and the room became too small. We moved to Gurugram, the pretext being a desire to be closer to ‘parents’ (my wife is from Delhi, and my mother continues to live in Muzaffarnagar). My next writing room was one of two in a rented apartment in Gurugram. I wrote my third book there. And now, where I am, is the room where I wrote my last book.

I like this room. I like this apartment. I am pained by the idea of leaving it, which is what we have to do in the next fifteen days: between my father's ninth death anniversary and my eighth wedding anniversary.

I have amassed a lot of books in the years in between, books which have travelled with us with every move. On my desk there is Lolita, 2666, A Swim in the Pond in the Rain, Life: A User’s Manual, and a few others. Then there are the four shelves full of books in other spaces inside the apartment. There are no recessed shelves here. There are no recessed shelves in any apartment in Gurugram. Recessed shelves are out of fashion. As are brass taps, fluted conduits, and heavy fans.

Rents have gone up. It is difficult to get something as good as this apartment for our reduced budget. Our budget is what it is because I have quit my job. Why? Because I’m a writer, and writers can do silly, whimsical things like leaving their day jobs. My wife and I aren’t exactly happy with our apartment search. It occasionally makes me regret becoming a writer. It makes me think of my mother, too. It makes me think of just how uprooted she must have felt while leaving that government-given bungalow. I was practically a visitor there, but if someone woke me up in the middle of the night and accessed the first image in my brain upon hearing the word ‘Home’, it would be one of that house. I imagine, as I leave one temporary home and look for another, what this process might have been like for my mother. She had no experience in such a thing.

The day moves ahead. The first day of the year; a beginning. I enter an online read-along for War and Peace, wishing someone would launch something like this for Ulysses too. I write two sentences in my next novel, one of them an arbitrary attempt to use an odd construction I came up with last night: ‘dehati demisemiquaver’. I have no idea what this might come to mean or what it might describe; I just like the sound of it, and its way of smashing together two words from thought- and language-universes as far apart as possible. Perhaps this betrays that I like alliteration. I like patterns in general. I force-fit them. I get used to them. I like living on in places I’ve lived in. I’ve read Lolita thrice.

*

In the evening I call my mother. A knot of feeling inside me wants to unspool. But life doesn’t work like the ends of movies. No unspooling finds its perfect words. I want to say how tired I am now, and how I know how tired she was then. This can never be said fully; this can never be understood fully.

She picks up. We share pleasantries. Then, when the conversation begins to peter out into weather and dinner, I ask her about Organic Chemistry by Morrison & Boyd.

‘There was this book of Chemistry,’ I say. ‘My book. I mean I bought it. But Ashu used it too.’

‘You guys took away most of your books, no?’ she says.

‘No, so, this one is called Organic Chemistry. Morrison and Boyd.’

‘Now how can I know from this? What did it look like?’

‘It was green. Dark green. With a ball-and-stick diagram on the cover. Is it with Ashu?’

‘No, I think it’s with me. Give me a second.’

Then there is a long pause. I hear her move inside her house. I hear a street dog’s faint barking. I hear her open a door. ‘Yes, or-ganic chemistry.’ she says.

‘It is with you?’

‘Yes, it is with me. It is home.’

***

This one hit the spot, both as a reader and a writer :)

overwhelming....invoked the feelings of dejection, nostalgia, loss, separation, guilt, hope.... all at one time