’it may be sporadic, but when there it is always intense’

On Flaubert’s Parrot, the futility and necessity of describing facial features, and how webby an amateur’s reading life progressively becomes

In late April, I finished Flaubert’s Parrot, my third Julian Barnes novel after The Sense of an Ending and Arthur & George. The novel is narrated by sixty-something widower George Braithwaite, a Flaubertian with a deep engagement with the French master’s work—the kind that can only be a product of love, and is, consequently, more often the domain of the amateur than an academic. George is a doctor by profession, which proves interesting in a good number of places in the novel. The novel’s premise is George’s mild obsession with identifying the real-life inspiration for Loulou, the parrot in Flaubert’s short story Un Cœur simple (A Simple Heart). In that story, Loulou becomes a profound emotional presence for the devout and simple-hearted Félicité, the protagonist, who even comes to see an overlap in the Holy Ghost and the parrot. George wants to find out whether the stuffed bird that once sat on Flaubert’s desk and found a mention in his letters, and which he reckons is the model for Loulou, still survives. His search leads him to two rival specimens housed in France (Flaubert lived in Croisset, a village near Rouen). Identifying which—if either—is Flaubert’s parrot becomes his quietly quixotic quest.

I read A Simple Heart in 2013, on a computer screen, inside a cubicle on the seventh floor of a corporate office. I had taken up a new job in an insurance company, and there was nothing for me to do for many months. So I took to reading books which would be possible to finish inside a day (I wanted that +1 on Goodreads), and which could be found online for free. While reading Flaubert’s Parrot last month, I felt the warm fuzz of recognition regarding Loulou—not anything concrete in the way of a remembered sentence, but in the way of ‘Oh yes, there was a parrot, yes’. Another novella I read the same way in 2013 was Pierre et Jean by Guy de Maupassant. That was a story about two brothers and a complication in parentage and inheritance or some such. I remember having a similar warm fuzz regarding Pierre et Jean when I read, in 2019, Udayan Mukherjee’s novel Dark Circles, which was about similar things. A reading life often makes such synapses—between year-of-reading, subject matter, and the remembered or misremembered quiddities of the writers one is reading and the self.

A Simple Heart was, in fact, my second Flaubert, after Madame Bovary, which I had read in 2010. The interesting thing is that I had started to read the book to learn French. That’s how foolhardy I was in my twenties: I would read Madame Bovary in French (with a French-to-English dictionary by my side, of course) to learn the language! I still remember the novel’s opening sentence in entirety (my terrible impromptu translation in parentheses » followed by Lydia Davis’ translation): Nous étions à l’Étude, quand le Proviseur entra, suivi d’un nouveau habillé en bourgeois et d’un garçon de classe qui portait un grand pupitre (We were in the Study when the Headmaster entered, followed by a new one dressed as a bourgeois and a classboy carrying a large desk » We were in Study Hall, when the Headmaster entered, followed by a new boy dressed in regular clothes and a school servant carrying a large desk). I wrote about this experience—rather, this stupid project of learning a language by reading a classic sentence by sentence—in a short story once, which became a chapter in my novel Neon Noon. The story is here if you want to read it.

By the way, the Nous/We that begins Madame Bovary is a really interesting one. One feels one is going to stay with this first-person plural narrator, made as a composite of students in a class, and that the knowledge constraints that apply to this group shall apply to the narration as well—which is to say, we don’t expect omniscience. Very soon, though—in fact, within the opening chapter itself—this first-person plural reveals itself as knowing the full history of the new student. By the second chapter, the pretence is shed, and we are practically with a third-person narrator. This narratorial shift is not made craftily but utterly casually. A contemporary novelist would sweat hard making such a thing happen; Flaubert does it unknowingly, almost. And to blind perfection. If one is willing to read well, it is impossible, really, not to doff your hat to Flaubert.

Becoming a Flaubertian like George Braithwaite of Flaubert’s Parrot is another matter. But take away the compulsions for a moment, and we find that George, too, is firstly a reader, one whose life is riven with all the synapses of a reading life. The details from George’s life that he narrates as he does his (self-consciously inconsequential) detective work congregate around the biggest loss in his life, the death of his unfaithful wife, Ellen. But these details, too, take their interpretative heft from matters Flaubertian. All things are linked. George is aware of the amateur’s advantage over the academic, especially the freedom to rely on common sense rather than prim pontification, which often loses a sense of proportions regarding what to dilate and to what degree (which is to say nothing of how frequently contemporary sensitivities are imposed on masterly work from the past). And so, assertions do abound; George frequently waxes eloquent on literary criticism, literary culture, and the correspondences between biography and fiction in a writer’s life. Flaubert’s Parrot is, it must be said, as satisfying as a book about literature as there can be, more than it is as a novel. But thankfully it has no glowing lessons for the reading classes. The book remains playful all around; its inutile-on-the-face-of-it subject is brought alive entertainingly, and the reader readily agrees to the entertainments, which include feeling like a voyeur in Flaubert’s personal life, following the strands of thinking around this or that literary matter, delectably dissing the contemporary here and there, and, generally speaking, acquiring a feeling for how hotly contested the past, whether it be literary or not, can be.

A good example of George’s engagement with Flaubert, his casual erudition, and his tendency to be thought-provoking regarding writers and writing comes from the novel’s sixth chapter, titled Emma Bovary’s Eyes. Here, George considers the critic and academic Enid Starkie’s assertion that Flaubert is careless of his characters’ outward appearance, ‘that on one occasion he gives Emma brown eyes; on another deep black eyes; and on another blue eyes.’ George finds the indictment ‘disheartening’, and cannot stop himself from immediately taking a dig at Starkie’s French accent, ‘swerving between workaday correctness and farcical error, often within the same word.’ But the amateur-in-love has to admit that he had never noticed ‘the heroine’s rainbow eyes’, and so he begins to bemoan Starkie’s fastidiousness, to find solace in how the professional critic is ‘cursed with memory’ and often treats a long-dead master as an old aunt who ‘hadn’t said anything new for years’…

Whereas the common but passionate reader is allowed to forget; he can go away, be unfaithful with other writers, come back and be entranced again. Domesticity need never intrude on the relationship; it may be sporadic, but when there it is always intense. There’s none of the daily rancour which develops when people live bovinely together. I never find myself, fatigue in the voice, reminding Flaubert to hang up the bathmat or use the lavatory brush. Which is what Dr Starkie can’t help herself doing. Look, writers aren’t perfect, I want to cry; any more than husbands and wives are perfect.

This is obfuscation, of course. Starkie is not, by pointing out the variation in Emma Bovary’s eye-colour, asking Flaubert ‘to hang up the bathmat or use the lavatory brush’. But the thing is, George is obfuscating with truth—or at least what reads as true. The points about the advantages of ‘the common but passionate reader’, which is the category that a reader of the Barnes’ novel is likely to assume for themselves, land believably. There is also more than a hint of the exact nature of George’s suffering: widower now, he had a wife who took lovers (like Emma Bovary, it is natural to point out). The reference to being unfaithful in the excerpt above, then to domesticity as a state of bovine companionship, then to the imperfections of husbands and wives—no extra marks for claiming that the composite metaphor here is derived from George’s marriage to Ellen.

Flaubert never married. And so he could have avoided, if we only stretch George’s insinuations, the fate of being an imperfect husband, and possibly even claim some state of perfection as a bachelor. But before we can go there, we have to salvage—or rather, George has to salvage for us—the pursuer of le mot juste. What must George do about the blemish cast by Starkie’s revelation of Emma Bovary’s multicoloured eyes? As it happens, George does have an answer, a perfect repartee to Enid Starkie, but, divagations being his mode, he won’t give it to us soon enough. He will mention a lecture by another critic, Christopher Ricks, themed ‘Mistakes in Literature and Whether They Matter’. A slew of mistakes by famous writers will then be mentioned.

Of these mistakes, the most shocking one for me—and curiously gratifying after the shock—was the one that mentioned Nabokov, about him being wrong about the phonetics of the name Lolita. I have read the novel many times, and each time I have tried to pronounce the name as Nabokov prescribes in the novel’s very first paragraph, ‘the tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. Lo-lee-ta.’ In these attempts I would invariably make the Ls less distinct than I imagined they needed to be, or make the first L sound indistinguishable from a hollow, involuntarily erumpent R, or just sound as if I was mid-gargle, especially at the moment of Lo. I often wondered if Humbert Humbert’s was indeed the right way to take the name, or if my tongue and palate were fused in a South Asian mould that just couldn’t produce a European delicacy. I was therefore glad to learn, you can well imagine, that someone across the channel did point out an issue with Monsieur N. My mouth, always offering an easier (to me) path for saying Lolita, might be alright, after all.

After deliberating on the mistakes of other writers, George arrives at a simple classification for mistakes in literature

External mistakes, wherein there lies a disparity ‘between what the book claims to be the case, and what we know reality to be,’ and

Internal mistakes, ‘where the writer claims two incompatible things within his own creation’

Whether the classification is George’s creation or loaned from Ricks’ lecture is unclear in the text. What is apparent is that internal mistakes are worse than external mistakes, for the anomaly cannot be ignored with the reliability of objective truth, and that Flaubert’s treatment of Emma Bovary’s eyes is an internal mistake.

Committed to whittling down Starkie’s assertion from different lines of approach, George sidesteps to a different, knot-blasting question: ‘does it matter what colour they are anyway?’ And in his nearly petulant response, he ends up highlighting important considerations for novelists, about the qualitative surplus (my words) of plain description, about the weight of a body part on characterisation, and about how focalised attention on an aspect of a whole tends to distort the whole

I feel sorry for novelists when they have to mention women’s eyes: there’s so little choice, and whatever colouring is decided upon inevitably carries banal implications. Her eyes are blue: innocence and honesty. Her eyes are black: passion and depth. Her eyes are green: wildness and jealousy. Her eyes are brown: reliability and common sense. Here eyes are violet: the novel is by Raymond Chandler1… I suspect that in the writer’s moments of private candour, he probably admits the pointlessness of describing eyes. He slowly imagines the character, moulds her into shape, and then—probably the last thing of all—pops a pair of glass eyes into those empty sockets. Eyes? Of yes, she’d better have eyes, he reflects, with a weary courtesy.

The emphases in the above segment are mine, to illustrate how, for novelists, ‘have to’ can run alongside ‘pointlessness’.

Some old readers of this substack might remember a similar concern raised in a story of mine, titled The Story, The Story, in which the neurotic narrator, in direct conversation with the reader, attempts to rationalise why he won’t describe the character K:

K is a human masculine idea—with height, weight, face, nose, penis, and other components. The story can describe these at length, to make you form an image of these things, but it chooses not to. Suffice it to say that K is the idea of the main man. External descriptions are fruitless, or at least some of them are. What is more important is filling this basic idea with character. Many inferior stories use large descriptions to fill in for character building. This story feels that to do so is wrong, utterly wrong. Why, you ask? Well, what if we say that K has “broad shoulders”, or “an aquiline nose”, or that he is “two meters tall”? These things denote something, right? These things make you provide a form to K. But does it stop at that? You imagine things, you extrapolate… no, impose… your form-value perceptions to K. You think you already know what he is like, what his character is like. And that is wrong; it is a flaw, a bad practice that many stories have proudly performed for too long.

To return to the colour of eyes. I have described women’s eyes many times in my own work (and never, I think, a man’s eyes, which is something I’m realising only as I type this). But given our context of mistakes in literature, let me confess to a description that I have, over the last couple of years or so, come to think of as a mistake. This is from my short story ‘Good People’, part of my collection Diwali in Muzaffarnagar. Ankush and Taruna, the couple at the centre of the story, are meeting for the first time. They have a conversation, and towards its end Ankush begins to be transfixed by Taruna, signalling the start of a romance:

Ankush nodded in agreement, noting the streaks of hazel in her dark eyes.

The emphasis has been added now. When I wrote the story, which must have been sometime in 2016 or 2017, I knew the word hazel as a nut, and thought of its colour as light brown (although in the above description, I surely meant a shade darker). I had no conception of hazel eyes, a category which, Gemini tells me, means ‘a captivating blend of brown, green, and gold hues, often appearing to shift colour depending on lighting and the surrounding environment.’ The image below, from Wikipedia, shows an example of what are termed hazel eyes—not the sort of eyes I had imagined for Taruna. There is an argument that my way of describing her eyes is vague enough to give me a pass, since I did not use hazel eyes and only ‘streaks of hazel’. But thought of another way, this can be—and is to me—even more embarrassing. What exactly are ‘streaks of hazel’ in an eye? Brown streaks? Green-gold streaks?

Why did I feel I had to impart a certain specific quality to Taruna’s eyes? Why couldn’t I see the pointlessness of the endeavour? In trying to show Ankush as infatuated, why did Taruna’s eyes have to suffer the writer’s ignorance? These questions trouble me, and taking a lenient stance (as one has to to live with oneself as a writer), I sometimes remind myself that to simply say ‘streaks of brown in her dark eyes’ would have missed a trick. The verb ‘noting’ demands that something be noted in the eyes; and it helps if it is something unique. So, voila, you may not have hazel eyes, Taruna, but you surely have streaks of hazel in your eyes. Deal with that!2

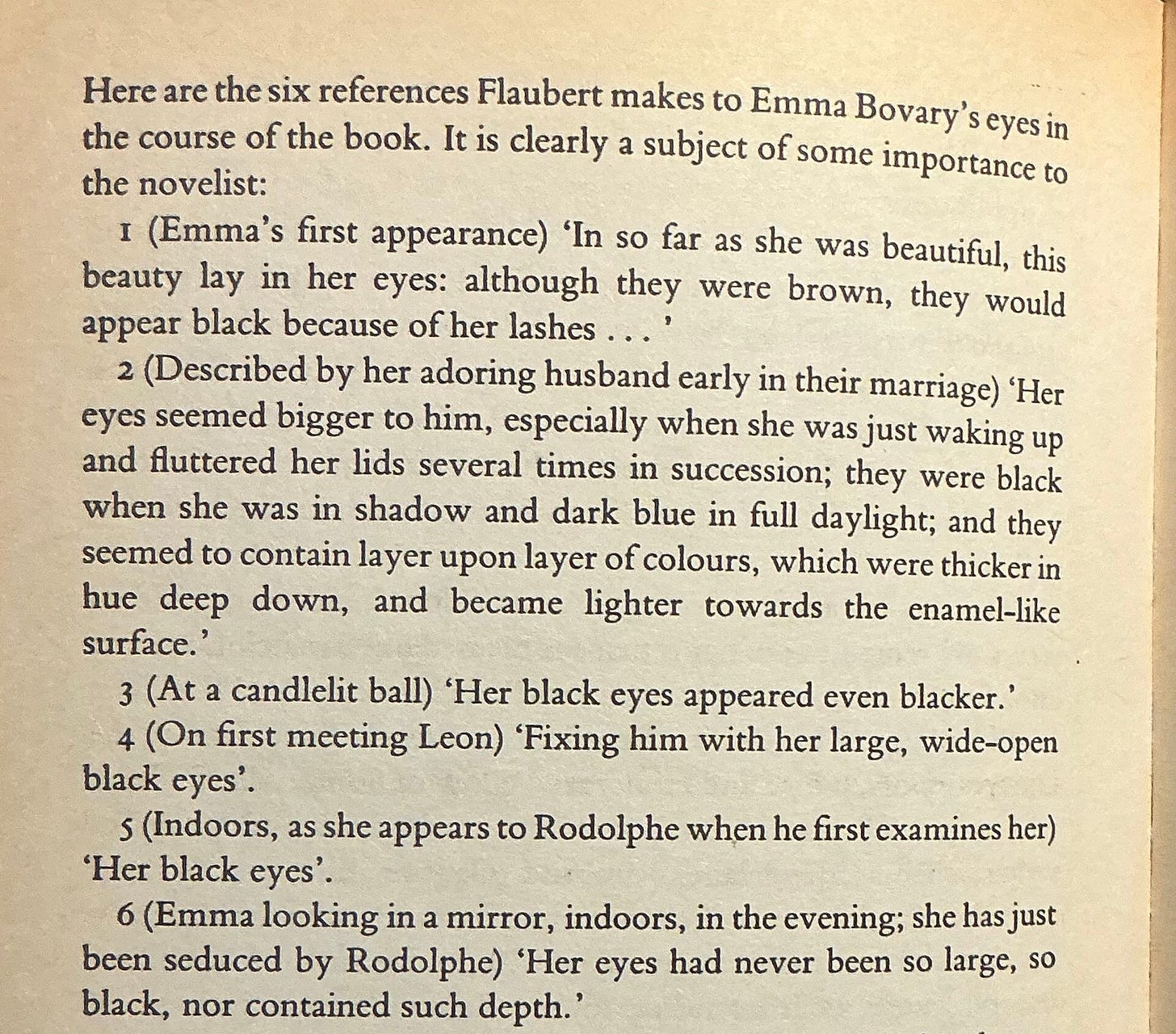

Back to George and Flaubert’s Parrot, and the question of Emma Bovary’s eyes. Could it be that Emma Bovary had hazel eyes, that simply shifted colour at different times, depending on the way light fell on them and the point from where the narrator looked at them? George doesn’t consider this possibility. He first takes another dig at Starkie, pointing out that her 1967 account of Flaubert’s life used a portrait of ‘Gustave Flaubert by an unknown painter’ in the preface, which was, in fact, a portrait of Louis Bouilhet (one of the persons to whom Madame Bovary is dedicated)3. This mistake on the professional critic’s part is amusing, no doubt, and may seem to have evened the score, but George goes further. Having ‘just reread Madame Bovary’, he lists all six mentions of Emma Bovary’s eyes:

Predominantly black, one would say; or, blacker and blacker as the novel progresses. They might have been hazel once, or maybe it is that the streaks of hazel in them are seen less and less by the characters who surround Emma, and, therefore, by the novelist. Is the progressive permanency of black suggesting some blackening in Emma’s character. It’s a question for another time, another book. For George, the above variation suggests not carelessness but extreme care; Flaubert was giving Emma ‘the rare and difficult eyes of a tragic adulteress […]’. If we believe this, there is no internal mistake. But what about an external mistake? Do such eyes exist in the real world? Flaubert doesn’t use the possibility of hazel eyes (one would have to consider if a French equivalent available to Flaubert); neither does George. George does better, in fact: he manages to go to a source that Starkie ought to have gone to: Flaubert’s friend and co-traveller, the writer and photographer Maxime du Camp. In his Souvenir Littéraires, Du Camp mentioned the woman on whom Emma Bovary was based, ‘the second wife of a medical officer from Bon-Lecours, near Rouen.’4 There’s a para-length description of this woman which George provides in full. It says the following about her eyes.

[…] her eyes, of uncertain colour, green, grey, or blue, according to the light, had a pleading expression, which never left them.

Hazel eyes, it seems, for the win! George ends the chapter with a charge of ‘magisterial negligence’ at Starkie, and asks us a simple question: ‘Now do you understand why I hate critics?‘

Hilarious. This really is something that Chandler, the master of the outlandish simile, could do

And yes, I won’t prohibit a future Hindi translator exploring the possibilities of ‘hazel eyes, hypnotise, kardi hain menu…’

Barnes mentions this discovery again in a review of a Flaubert biography published in 1989. I wonder if Starkie’s error was his discovery.

Emma Bovary was second wife to Charles Bovary, a country doctor,

Really good article! With each short story and non-fiction piece you may be moving away from your novelist dreams! I particularly appreciate the observation that Flaubert's Parrot has no real lesson for the reading classes, remaining playful all the way through. I read this before I read anything by Flaubert and now might want to revisit Bovary and her world.

Delightful ruminations, Tanuj - a mosaic of ideas woven deftly together, and the excursions into your own writing are a charming touch. Loved the 'hollow, involuntarily erumpent R, or just sound as if I was mid-gargle' bit, and the the way you've used 'synapses', occasioning both surprise and pleasure. It'll be a delight to read Flaubert's Parrot whilst channeling this essay in my thoughts.