A couple of days ago, at an evening get-together at a friend’s house (the friend is also my agent), I met an author who will soon have a new novel out. To some of the other people present in the room, whom I didn’t know from earlier, this author introduced me as a fellow author with four published books and an erstwhile career in insurance. What made this introduction unique is the comment the author added about my work: ‘each of his books is completely different from the other.’ That no two books are the same is a truism, but what this author meant in this case, in the way of paying a compliment, was presumably that each of my books differs from the other so significantly—in location, style, tone, subject matter, socio-economic milieu, genre conventions adhered to or toyed with, et cetera—that it is a fair challenge to give credence to the fact that they have all been written by the same author.

There is good evidence—generated all by myself—for me to agree with this. My last novel, Manjhi’s Mayhem, was also my first crime novel, and had a distinctly working-class milieu, something that hadn’t been the case in my work until then. The novel before this one, The Machine is Learning, would perhaps be categorised as literary fiction, and its cast belongs almost entirely to the high end of the corporate world, a world that would be alien for the cast of Manjhi’s Mayhem (even though both novels are set in Mumbai).

And so, in a light-hearted response to the author’s introduction, I narrated how I had recently anagrammed my name to create a pseudonym and now actually wanted to write a romance novel (set in IIM Ahmedabad, no less) to be published under that new name. That I am actually serious about the idea and do very much intend to pursue it at some point perhaps didn’t become a part of my delivery.

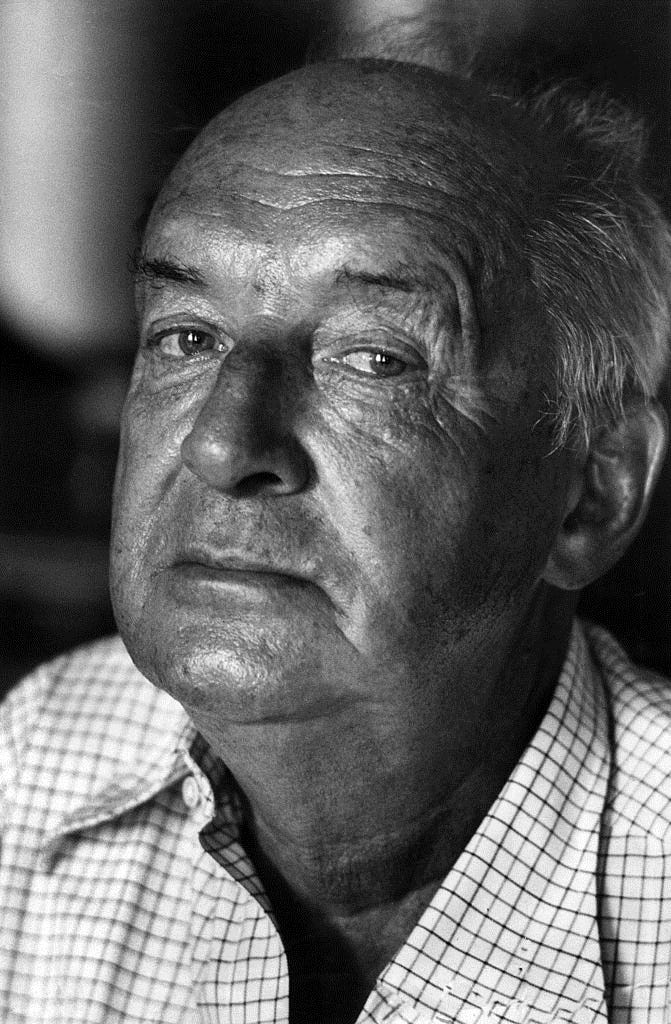

Without hazarding a claim about whether I am a good or a bad (or a barely decent or a less than competent) writer, I think it might be possible to still self-proclaim that I am a reasonably versatile writer. The work is there; it kind of proves that (even when this is the only thing it proves). Versatility isn’t always considered a healthy trait among writers. Here’s Vladimir Nabokov’s famous take on the matter:

Derivative writers seem versatile because they imitate many others, past and present. Artistic originality has only itself to copy.

The quote is, in itself, a complete assertion, and a resoundingly convincing one at first sight, even if one is at a momentary loss to conjure examples that would satisfy either of its polarities. Nabokov sets up versatility in opposition to originality, and even though it is not stated that Nabokov conceives of originality as being totally outside the engine rooms of imitation, the suggestion is obvious; it stays with us that way. The contradiction implicit in the second sentence (surely an original work of art can bear only so much copying before the later works appear bleached of originality, even if said imitation were being performed by the originator) somehow adds to the verve of the whole. We don’t even register it when we read these two sentences; we feel simply that a profound truth about art has been revealed to us.

A bit of consideration for versatile imitators, then. Decoding others’ works, imitating it in earnest, and inevitably imbuing the process with an error function, a function that contains their own parcels of genius or talent or mediocrity, or even just shadows from their unique personality, background, and/or neuroses—is such a process too different from the causeways that Nabokovian ‘artistic originality’ takes? To turn the question less abstract: was a declared dislike of mystery/detective novels, especially the work of Agatha Christie, related to how several of Nabokov’s novels featured murders or suggestions thereof? And Lolita—with its three all-America road trips, its paragraph-length take down of Westerns, all its alliteration and assonance, and Humbert Humbert’s unique voice and vocabulary, with stated predilections for ‘logomancy and logodaedaly’—does it owe nothing to the work that came before; is it never, at no place, an exercise in utilising, or playing with, elements already practiced and deployed by others, and, in that sense, an exercise in imitation? Back again to abstractions: is it impossible to come to artistic originality from a collage of imitation?

It might be useful to point out here that Nabokov’s comment was made in an interview (the Paris Review interview), in response to the following question:

Clarence Brown of Princeton has pointed out striking similarities in your work. He refers to you as “extremely repetitious” and that in wildly different ways you are in essence saying the same thing. He speaks of fate being the “muse of Nabokov.” Are you consciously aware of “repeating yourself,” or to put it another way, that you strive for a conscious unity to your shelf of books?

Even if we see Nabokov’s response as pat, it is clear that he is not in disagreement with Brown. But here we find a new concept amidst the proposed polarity between versatility and artistic originality, one that no number of equivalences in the processes at play at either end can resolve: unity. Clarence Brown, in his essay titled Nabokov’s Pushkin and Nabokov’s Nabokov, sees a unity in Nabokov’s work, underlying not only among the novels but other work too, including his translation of Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin. This assertion is backed by, among other things, an analysis of style: “He [Nabokov] can neither think nor see without etymologizing the universe,” Brown writes. Since this method of thinking and seeing has its total hold over the writer, the corollary that they can do nothing but repeat themselves follows naturally. That this writer is aware of their own singularity doesn’t make it any less singular; all it does is make it probable for it to find (beautiful) expression. “The only real number is one, the rest are mere repetition,” Nabokov writes in his novel The Real Life of Sebastian Knight; Brown quotes this line twice in his essay.

So here I am, back on the other end of the pendulum’s swing. If a certain singularity is the only state worth aspiring to as far as the matter of art goes, and if said singularity, once reached, cannot but lead to repetitive pulses, then versatility—including my versatility, of course—is a symptom of failure in art. Perhaps the injunction ‘find your voice’, one that upcoming writers tussle with because it’s a mystical, near-spiritual statement that offers nothing in terms of direction, is clearer when read as a posture against this thing called versatility. And perhaps my long-standing allergy to the concept of writerly voice—nobody has ever been able to explain it to me in a way that would differentiate it from narratorial voice—an allergy that I have allowed to be visible in litfest panels, in DMs, and in the classroom, is a psychological response to a latent awareness of not having found my own. Why the hell am I even thinking of writing a romance novel?

The whole matter comes down to whether or not there is a value in shape-shifting? Just as the imposition of unity on all perception (whether enlivened in etymology or theme, or argued through scientific pickings) can lead to a singularity in art, can the exact opposite view, one that regards a fiction writer’s task as a play of verisimilitude and ventriloquism, and results in a certain degree of disunity across works, even masquerades with multiple signatures—can this result in art too?

In my teaching, I invite—perhaps it is more accurate to say that I strongly nudge—students to ‘alertly imitate’ the works selected for the classes. For originality, I rely on prayer, along with ‘intentionality’ and the ‘error function’. The rationale is simple. The first movement of imitation is to arrive at a degree of understanding, to essentialize another’s work to a model, a diagram, picture, a flowchart, or just a mental fuzz that has the tint of meaning only for the one whose mind it inhabits. In this movement itself, one cannot but escape the error function. A misreading has already taken place. And a paradox is set in motion, because the imitator, in making an arduous attempt to make their reduction represent the text’s whole, establishes an insurmountable difference between the two. To the next step of imitation, which culminates in the production of ‘original’ text (through an expansion of the reduction produced in first step), if a degree of ‘intentionality’ can be added—an ‘intentionality’ informed by the subjective world-view and experience-bank of the imitator, and their specific linguistic neuroses or limits, which is the closest I have come to understanding voice, and which is, in fact, the conscious version of the same things that I have called the error function—then the artefact thus produced is in the zone of new. Having read dozens of short stories written through the aforementioned processes, I would say the result is good.

To the degree that I’m conscious of my own behind-the-scenes turmoil, I believe I do use a fuzzier, less-schematic, in-the-mind-only version of the process for my own work, though only to fill parts of a whole. There is a great degree of intentionality, and that intentionality is informed not just by personal history but also by personal publishing history, a sense of a body of work. And my pride in my profession finds a certain ease among negative formulations: I am neither T, the sex-trip-seeking monster of Neon Noon, nor Gunjan, the arch-pragmatist of Compassionate Grounds, nor Saransh, the ethically troubled yuppie of The Machine is Learning, nor Sewaram Manjhi, the Dalit immigrant worker and enforcer of Manjhi’s Mayhem. I am their voice. Like Nabokov, I’m interested in soiled aristocrats; but I’m also interested in several others.

I am large. I contradict myself. I contain multitudes

Singularity has no meaning if the artist is aware of it. And, perhaps its limitations too. This is a brilliant piece, and I've suffered from the place of various selves and as if it were the death of art when you watch an Amitav Ghosh with a single-minded vision, yet with the ability to tell all-encompassing tales of migration, loss of habitat or home...

One arrives at singularity. Your writing on provincial life and your moorings in urban settings perhaps have contradictions. But those variations bring subjectivity and unity in seeking our own truths and clashing selves. And so, the romance novel comes into picture, I suppose, in buoyance. :)