Joy in Sebald

… and a couple of discoveries that, I sadly discovered, had already been discovered

Some news: my short story Khalil, published in Mint Lounge’s ‘War and Peace’ Fiction Special in January, has been translated into Hindi by Bharatbhooshan Tiwari and is up on the Samalochan website. My immense debt to Bharat bhai continues to swell.

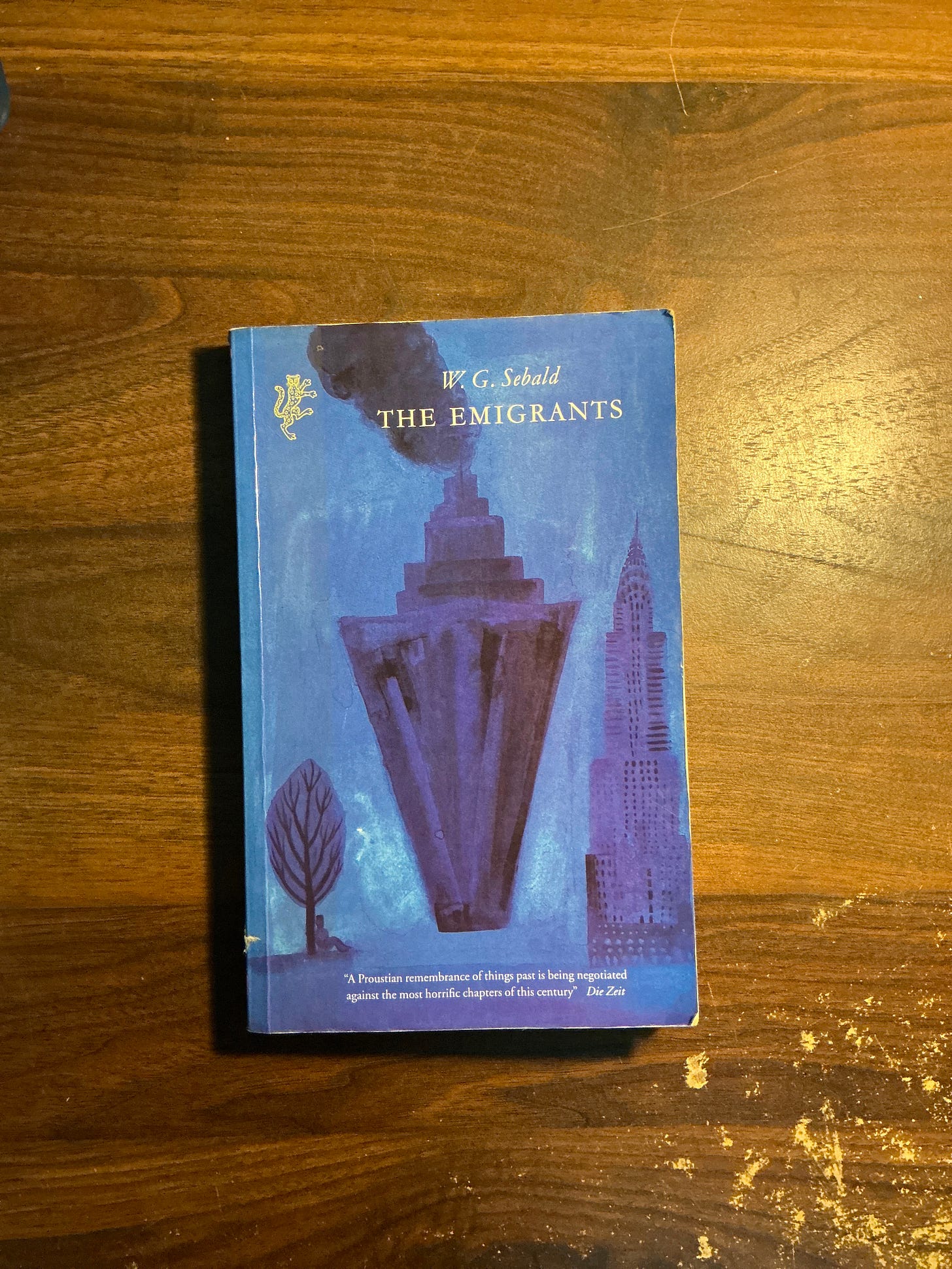

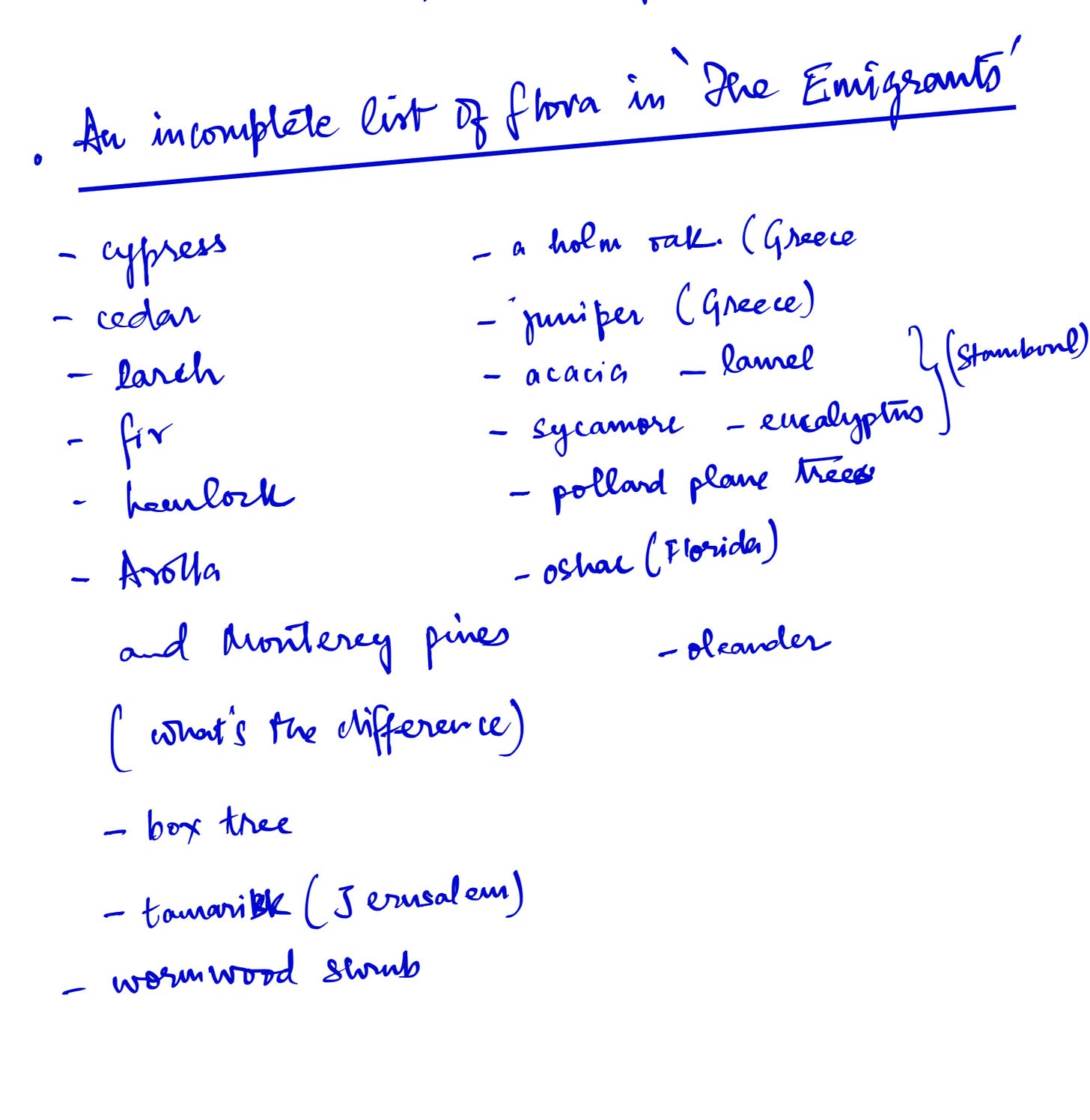

Earlier this month, I finished reading ‘The Emigrants’ by W.G. Sebald. This was a conscious return to Sebald in some ways, whose ‘The Rings of Saturn’ and ‘Austerlitz’ I had read more than ten years ago. I must have, at that time, turned Sebald’s style and sensibility to some essentials—that he wrote what can be called ‘documentary’ novels; that there are pictures in his work; that the sentences are long; that his narrator can get into narrating someone narrating someone’s story from memory, such that nested constructions like ‘he said, she said, Austerlitz said’ are encountered; that the Holocaust is a constant negotiation in his poetics; and others. All of this is very much present in ‘The Emigrants’ too. But one of the things I noticed with more acuity this time was Sebald’s insistence on describing flora, and how, for the primary Sebaldian narrator, who militantly eschews any significant lapse into describing a personal feeling, being amidst trees and shrubs and wild flowers, and assiduously naming all that can be named and placing all that can be placed in relative order, becomes a way of signifying personal feeling that is distinct—even as it remains deep in the shadows, so to speak—from the affect that these descriptions are to create in conjunction with what usually follows them: long discourse with another person. Overall, in any single narrative pulse, Sebald can be argued to be following the modality of the interview as a full dialogic scene, wherein the interviewer describes, first of all, the space where they meet the interviewee, and then the look of the interviewee, including their attire, and then goes on to report the conversation, with an alertness for catching gestures and shifts of mood. But Sebald’s interviewees remember more, narrate more, and produce more artefacts for further research than most interviewees in fiction. There is an excess, so to speak, which borders on the incredulous, and which Sebald deftly makes supportable through an abandonment of the norms of rendering conversations in fiction. No inverted commas, no para breaks, no adjectival weight in the dialogue tags. The excess in the conversation, thus, becomes constitutive of an essay more than it is constitutive of a fiction.

But when I speak of flora description as signifying the primary narrator’s personal feeling, I’m speaking of an excess that exists before the conversation begins. The narrator’s feeling in these passages is, according to me, that of relief. It is as if being in nature provides him an interregnum from pervasive melancholy, where the ability to name goatsbeard as goatsbeard and tamarisk as tamarisk becomes its own end, and where the impositions of narratives-about-to-be-discovered—whether they be the narratives of the century and its faults, with the Holocaust bang in their middle, or personal narratives of gradual collapse—are momentarily at bay. I must add that the noticing and naming in Sebald is not unique to flora, and often descriptions of all kinds are so intermingled that to extract a segment as a passage about so-and-so and so-and-so only is difficult. Landscape, natural or man-made, is described, cityscapes are described, buildings are described, interiors are described, people and their attires are described. Most of these are, however, presented as mutable or shown as having already mutated, and are one observation away, if they are not there already from the get-go, to acquire through association or historical exposition a certain narratorial charge of accreting ruin. Only in nature does the Sebaldian narrator find the pre-historic; only in nature does he have respite from his dominant feelings—and so, only in flora descriptions, whether they be a whole section or a parenthesised sentence, does the reader get a hint of joy in Sebald.

I made some discoveries while reading ‘The Emigrants' whose thrill vanished as soon as I googled the conclusions, but which might nevertheless be worth mentioning here. Early in the novel, I had sensed that Sebald was trying to do some associative mapping with the figure of Vladimir Nabokov, using the Russian’s reality of being an emigré, being a lepidopterist, and being a road-tripper in America to sprinkle artificial recurrences in his book’s four disparate parts—disparate, especially, if we consider suicide and depression as not being enough of a thematic glue. I was, of course, not the only one to have noted Nabokov’s apparition in ‘The Emigrants’. Academics have written about it. Though I'm still convinced—for there is no data that can possibly disabuse me of the notion—that I sensed Sebald was about to do something grand with Nabokov and butterflies and Montreaux and American landscapes as early as on page 16, when he gives us a photo of the Russian with his butterfly net.

Apart from Nabokov, there was something about Naipaul too. The opening of ‘The Emigrants’ first part has the narrator and his partner looking for a dwelling place in the English countryside. They arrive at an estate, and the description that Sebald gives is roving and comprehensive (with, of course, a pause around flora whenever possible). It reminded me acutely of the similarly roving and comprehensive opening of Naipaul’s ‘The Enigma of Arrival’, which had, in point of fact, the Naipaul stand-in doing the same as the Sebald stand-in here: walking around an estate in the English countryside. There is something to read into the fact that Naipaul fails to mention his wife in the entire novel while Sebald mentions his partner at the earliest opportunity, but I'll let that pass for now. Anyway, I googled if anyone had noticed this similarity and, needless to say, they had. Naipaul has even been casually called, as I learnt, ‘the Sebald before Sebald’, which I think is a compliment Naipaul would have neither desired nor deserved, for in everything other than ‘The Enigma of Arrival’, his mode is decidedly different from Sebald’s.

Enjoyed the essay, Tanuj. Thanks. Sebald's style is hard to characterise. The patterns are stable enough --it's as if he keeps writing the same novel-- but his style is also so unique, it always feels a little unfamiliar.